Banning new sales of ICVs by 2035 approved: what now?

On 14 February 2023, the European Parliament gave its final approval to a 2035 sales ban on new carbon-emitting gasoline and diesel vehicles, with the goal of removing them off the continent's roads by the middle of the century.

Despite resistance from conservative MEPs, the largest group in the parliament, member states of the European Union have previously approved the legislation and will now formally nod it into law at an upcoming ministerial conference. The bill's proponents had argued that it would provide European automakers with a specific timeline in which to switch manufacturing to electric vehicles with zero emissions and encourage investment to fend off competition from China and the United States. This in turn will support the ambitious goal of the European Union to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and create a "climate neutral" economy.

"Let me remind you that between last year and the end of this year, China will bring 80 models of electric cars to the international market. These are good cars that will be more and more affordable, and we need to compete with them. We don't want to give up this essential industry to outsiders." EU vice president Frans Timmermans warned MEPs.Opponents countered that hundreds of thousands of jobs are in danger and that neither European industry nor many private motorists are prepared for such a significant reduction in the manufacturing of internal combustion engine automobiles.

Havana effect

The switch to electric vehicles in Europe will result in the elimination of hundreds of thousands of jobs throughout the entire supply chain or about 600,000 employments for the entire EU. 12,7 million direct and indirect jobs, or 6.6 percent of all EU jobs, are supported by the automotive industry in Europe. The EPP group foresaw what it called the "Havana effect," in which Europeans would continue to drive old polluting cars after new sales were outlawed because they couldn't find or afford an electric vehicle. Some claim that competitors of Europe, such as the United States, build vehicle batteries elsewhere, but Timmermans countered that production in Europe would rise as a result of EU-supported investment. The relevance of the prohibition in lowering emissions and pollution was emphasized by green MEPs.

"Our proposal is to let the market decide what technology is best to reach our goals," said MEP Jens Gieseke, a member of the centre-right European People's Party.

However, the European auto industry did not make a strong effort to campaign against the rule because numerous businesses were already competing for market dominance in the electric vehicle industry. Yet, the United States has disclosed a massive plan to subsidize the green transition of its own economy with government handouts since the law started its journey through the EU parliamentary process. This has sparked worries in Europe that its US rival could steal jobs and investments from the industry, which produces batteries and electric vehicles.

As energy prices rise and more environmentally friendly traffic laws become the norm, buyers are moving away from CO2-emitting vehicles, with about 12 percent of new cars sold in the European Union now being electric. The largest auto market in the world, China, wants at least half of all new vehicles to be an electric, plug-in hybrid, or hydrogen-powered by 2035. The Strasbourg assembly approved bill 340-279 with 21 abstentions.

A new scenario for remanufacturing

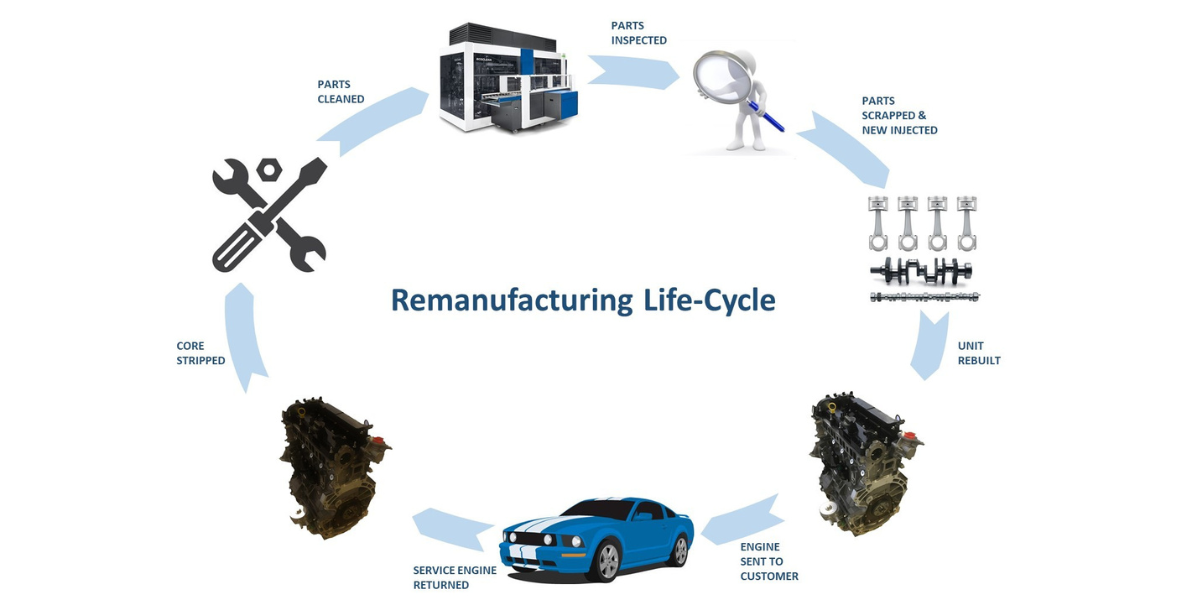

The technicians who up until now have devoted their careers to the creation and remanufacturing of endothermic motor vehicles, which include a variety of parts that are absent from BEVs, such as the engine and its components, are now more frequently required to work with an entirely new category of technology represented by an electric vehicle. This creates two possible outcomes: on the one hand, the requirement for new skills (refresher courses), which enables them to be ready to manufacture and remanufacture BEVs, whose components are different and less compared to the ICEVs; and, as previously observed, on the other hand, a potential risk of labour loss.

Because it takes longer to build an internal combustion engine than an electric engine, for example, fewer mechanics are required: according to some data, it takes less than three workers to build an internal combustion engine. So, it may be presumed that the situation is the same when trying to remanufacture the batteries and other parts of a BEV. So, it is uncertain how the market will respond. Given that alternative fuels like LPG, CNG, and hydrogen might help reduce pollution caused by internal combustion engines, it might be preferable for a while to manage the coexistence of electric and conventional mobility well.

Gianmarco Giorda, general manager of Anfia, the Italian Association of the Automotive Industry, one of the most important markets in Europe, underlines that “some of the companies will have to convert to other sectors. On the one hand, it is necessary to focus on active reconversion tools but also to imagine tools such as social safety nets for the transition that will have to accompany many companies that, even if they want to, will not have the opportunity to convert to other areas of the auto sector.” The association is certain that the additional jobs brought about by the switch to electricity would never be sufficient to offset those lost due to the changeover itself. “This transition is okay to do, but it is very likely to lead to a negative balance in terms of employment in our factory if corrective measures are not applied“, Giorda concluded.