We saw in my last post how end-of-life (EoL) policies drive the auto industry towards recycling. In this post, we will not only look at what those EoL policies are, but also leaf through some of the policies related to the production phase, point of sale, and use phase and see how these policy levers create an impact as the product goes through its journey from manufacturing all the way to ultimate recycling. It is a slightly longer read, so please bear with me.

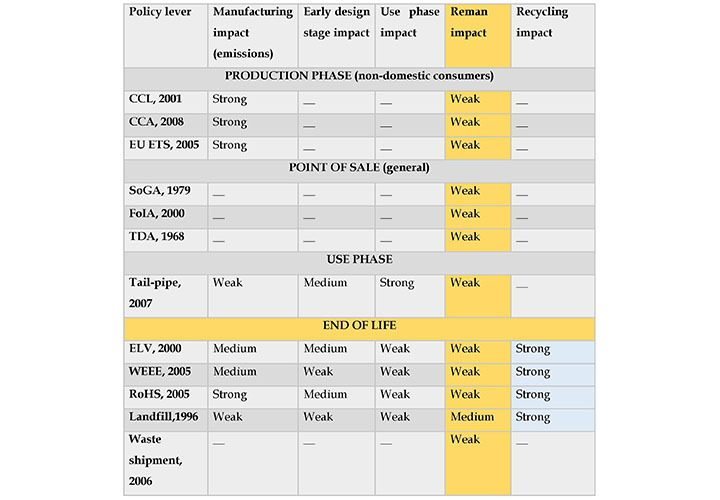

While doing my research, I came across an interesting study conducted by Walls (2006) that looked at the impacts of American recycling policy instruments on production, design and recycling stages. I could not think of a better way to illustrate the various policy impacts within the EU context, so I adapted the table format from the Walls study.

The first column lists down the studied policy levers, and the columns two through six, list down the various stages in a product’s lifecycle. I have explained the various terms in the glossary just after the table.

Glossary to the Table 1

CCL: Climate Change Levy – Tax on energy for non-domestic users

CCA: Climate Change Agreement - Voluntary agreements made by UK industry and the Environment Agency to reduce energy use and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions

EU ETS: EU Emissions Trading Scheme – A cap and trade international system for trading greenhouse gas emission allowances

SoGA: Sales of Goods Act

FoIA: Freedom of Information Act

TDA: Trade Descriptions Act

ELV: End of Life Vehicles directive

WEEE: Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment

RoHS: Restriction of Hazardous Substances

The Climate Change Levy, Climate Change Act and the EU ETS primarily impact the production phase and are related to the carbon emissions. Most non-domestic users of energy (manufacturing, energy intensive businesses etc.) within the UK adhere to these three policy levers for the use of fossil fuels. Even though they do not have any direct bearing on the use or post-use phase, they do create an indirect impact on remanufacturing.

When purely looking from carbon emissions viewpoint, a remanufacturing activity (assuming it is in-house) will push the emissions higher since a remanufacturing operation will be treated as any other manufacturing facility, and the current EU ETS, CCL, CCA legislations account for only fossil-based fuel consumption. The raw material and embodied energy savings accrued by remanufacturing parts are not accounted for in any category of legislations.

This may mean, even though the sales of the new parts are going down (when reman sales are going up), the carbon emissions are going up, as these legislations only capture the emissions resulting from fossil-fuel use and don’t capture the raw material consumption. Hence, we see a negative or weak impact on remanufacturing resulting from production phase policies.

The Sales of Goods Act impacts remanufacturing indirectly to the extent that a manufacturer is responsible for making quality and reliable products. Since this act affects the retailer who sells the product, the cheap perception associated with reman parts is not an incentive for retailer to sell reman parts. Further, if there is any defect in a reman part, then it is the retailer who is responsible. Hence, a negative impact on remanufacturing from a retailer’s viewpoint.

The Freedom of Information Act impacts remanufacturing to the extent that there is a lack of right of access to design information to the remanufacturer from the OEM’s. This forces independent remanufacturers to reverse engineer the products which can turn out to be costly and time consuming and thus dis-incentivizing the remanufacturing activity.

The Trade Descriptions Act is primarily set up for the protection of consumers so that they are not misled by claims that may be not present in a product or are present but are not presented to the customer in a correct manner. This is especially true in the case of in-warranty replacements, where VM dealers replace in-warranty failures with reman parts instead of new parts after 3 months into the warranty (may vary for different VM’s). While this significantly reduces the warranty costs for the VM, the customer is not made aware at the point of warranty replacement. This could have serious implications, if the customer later finds out that a particular part was replaced by a remanufactured part and not a new part, which can damage the reputations of not only the dealer but also the VM and the remanufacturing industry in general. This drawback was also pointed out during the interviews I conducted with some of the dealers.

EU Reduction of Pollutant Emissions from Light Vehicles Act of 2007 (Tail-pipe emissions): The remanufacturing phase occurs during the entire use phase of the vehicle when it is owned by the customer. While the tail-pipe emissions law does capture the use phase emissions and does push the VM’s towards producing energy efficient engines and drive trains and construction of light weight architecture, no policy, EU or otherwise, credit the environmental and material savings resulting from the remanufacturing activity. Furthermore, no incentive via financial mechanism is provided to credit the manufacturer (VM or tier 1 OES), for remanufacturing. The 60-85% of material and resource savings attributed to remanufacturing are not captured and this dis-incentivizes the VM’s to embrace methods such as design for remanufacturing (DfRem) which are enablers to remanufacturing.

End-of-life Vehicles Act of 2000 directive’s main aim is to increase the re-use and recovery (via recycling, regeneration etc.) of vehicles those reach their end of life. The rate of re-use and recovery should be 95% in average weight per vehicle (Directive 2000/53/EC). The ELV act has no mention of remanufacturing specifically and can also cause confusion since it is not explicit in naming which forms of recovery are required.

Of the 25 companies that I spoke to (including remanufacturers, OE suppliers, OE manufacturers and academic researchers) close to 80% of them believed that ELV directive either does not encourage remanufacturing or simply causes confusion for manufacturers as remanufacturing is not addressed in those directives. It is interesting to note that some of the companies who do perceive that ELV policies encourage remanufacturing, say so only to the extent that ELV directive may be able to yield core which is the raw material in remanufacturing.

Waste Electrical and Electronics Equipment (WEEE) Directive of 2002 and Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive of 2003: The WEEE and RoHS directives were established to address the problems of complex materials and components that go into manufacturing the electrical and electronic equipment. At a high level, WEEE directive achieves three main goals:

Other research has shown that WEEE directive has led to increased recycling rates and reduced waste disposal, supporting the ‘push towards recycling’. The research also showed that there is no data available demonstrating that WEEE has caused any effect on manufacturers to adopt strategies that consider environment during the design stage.

This can lead WEEE directive to cause more and more equipment to be scrapped well before its time and even though the directive encourages re-use, it is difficult to quantify the re-use levels (as the original producer in most cases will not have the visibility at that point) and thus is difficult to measure those levels in favor of overall recovery targets laid down by other directives.

With regard to RoHS directive, it requires manufacturing operations to be separate for products that contain RoHS restricted substances from those that don’t. Since remanufactured products are in general, older and were produced before these directives came into effect, they would contain restricted substances and hence would not only have to be remanufactured in separate facilities but also does not work well in the favor of remanufacturing as the legislation is geared to remove those substances and remanufacturing is putting those substances right back into the use phase, by extending the product’s life that do contain such substances.

The Landfill tax does impact remanufacturing in a positive way only partly, as the tax on landfill causes the manufacturer to look for ways of reducing the landfill and remanufacturing is one of the options to avoid the tax.

EU Waste Shipment Regulation of 2006 requires no waste to be transported to non-OECD countries and outside of EU. While this is a right regulation, cores or the old units are often taken as waste and fall in this regulation creating a barrier to ship remanufactured parts internationally. The regulation also does not allow access to cores from other countries as they get categorised as waste. In my research, I found this to be a constant challenge that OEM’s have to face resulting from this regulation.

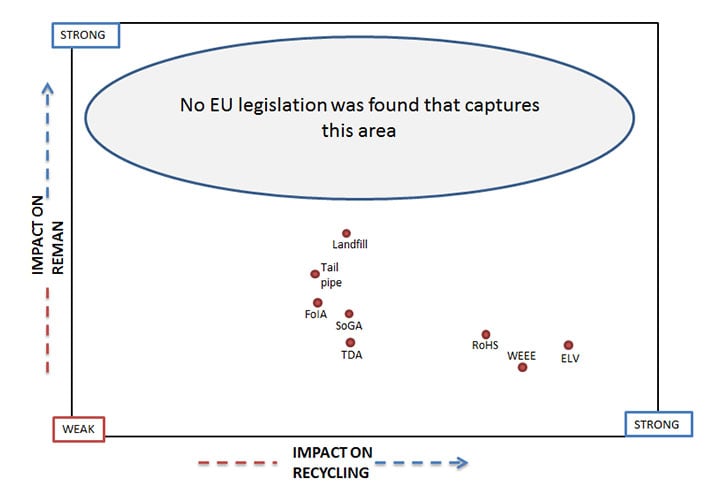

It is well understood that recycling is an additional cost activity for manufacturers and hence governments provide recycling discounts (which can be termed as perverse incentives) to manufacturers. Referring to Walter Stahel’s work in the late nineties, he argued that shorter the reverse loop, higher the gains, both in terms of energy and material usage. Re-use and remanufacture have shorter loops than recycling and yet recycling is the most pervasive activity which is not only costly but also highly energy intensive. All the policies that we saw in this post have weak impact on remanufacturing with the EoL policies strongly skewed towards recycling. This is due to the incentives and policy instruments that have caused such a high uptake of recycling. Thus, a similar approach to remanufacturing may also yield similar results.

The analyzed EU directives drawn out in the table 1 don’t have favorable impacts on remanufacturing and as shown in figure 1 there is no law or directive that categorically addresses the material and resource savings that remanufacturing brings by way of avoided virgin material and energy usage.

So, will a policy change that incorporates remanufacturing be the solution? If so, what kind of policy and at what phase of the product’s lifecycle should it fall under? Does a remanufacturing policy have to come at the expense of recycling? We will look at some of these questions and try and gain some more understanding along with some recommendations based upon my research. All of this in my 3rd and final post of this series.

Share your remanufacturing stories with us

Do you have an innovation, research results or an other interesting topic you would like to share with the remanufacturing industry? The Rematec website and social media channels are a great platform to showcase your stories!

Please contact our Brand Marketing Manager.

Are you an Rematec exhibitor?

Make sure you add your latest press releases to your Company Profile in the Exhibitor Portal for free exposure.