Batteries not included

With sales of electric vehicles gathering pace, the automotive reman sector is checking out new opportunities. But, as Andrew Stone finds, remanufacturing batteries may not be that easy.

Slow off the starting line, the global electric vehicle (EV) sector is now starting to accelerate into the mass market. In the US, production of Tesla’s model 3 - set to be the world’s first ‘affordable’ mass-market, long-range EV - looks to be hitting its stride after initial teething problems. In China, meanwhile, the electro-mobility revolution is in full swing with hundreds of thousands of electric cars, trucks and buses now rolling off production lines annually.

As the global EV vehicle parc grows (it is set to reach 2.6 million in 2020, according to Navigant Research) so should the remanufacturing opportunities. In theory, EVs could offer significant scope for reman since they can be designed from the ground up with modern circular economy objectives in mind.

Reman potential

And it is batteries, representing up to 40% of the value of an EV, that will offer much of the potential for reman. There could be 11 million tonnes of used EV batteries by 2030, according to an estimate from Canadian battery recycling startup Li-Cycle.

Perhaps the best-known – and, in terms of media coverage, certainly the most colourful - name in this nascent industry is Tesla. The company’s long-professed aim to create a ‘closed loop’ battery process - together with China’s recent legislation mandating EV battery recycling or reuse by August 2018 - suggest it is just a matter of time before a big market in EV battery remanufacturing, reuse and recycling takes off.

There is some evidence of activity in this regard. Mercedes-Benz is building a $91m remanufacturing plant in Shanghai with a focus that will include EVs, while leading Chinese EV maker BYD has announced plans to open an EV recycling centre.

The economics of remanufacturing are yet to be established but there are some clues when it comes to re-use. In Japan 4R Energy Corporation, a Nissan and Sumitomo Corp JV, will reassemble a few hundred battery modules annually from the first-generation Nissan Leaf, where the used pack’s overall energy capacity has fallen below 80%. It will sell them for $2,855.51, roughly half the price of brand-new replacement batteries.

Repurposing costs

Battery repurposing costs, meanwhile, can be as low as US$20/kWh, according to the 2017 paper Repurposing Used Electric Car Batteries: A Review of Options. So this would mean, theoretically, that a 40kWh capacity battery pack you could expect to see in the current ‘longer’ range Renault or Nissan models might be as low as $800 to repurpose - for example for use as a stationary battery pack used to store power from solar panels.

Another study, Second Life for Plug-In Vehicle Batteries by the University of California, Davis Plug-In Hybrid & Electric Vehicle Research Center, estimated repurposing costs for several different sizes and models of plug-in electric vehicle battery packs, including a Chevy Volt pack ($1,150) and a Nissan Leaf pack ($1,780) - far lower than their original prices.

Despite all this potential and the apparently advanced activity underway, a viable EV and battery remanufacturing and reuse market right now seems a long way from emerging. The immediate problem is the lack of used battery packs in circulation, preventing any sort of remanufacturing or repurposing activity from taking place at scale.

As the number of used packs increases there are further problems. The business model is as yet unclear since cost-effective processes required for remanufacturing are very far from being realised. It is even rumoured that one EV manufacturer is simply storing its used packs with no plan yet for what to do with them.

Manual challenges

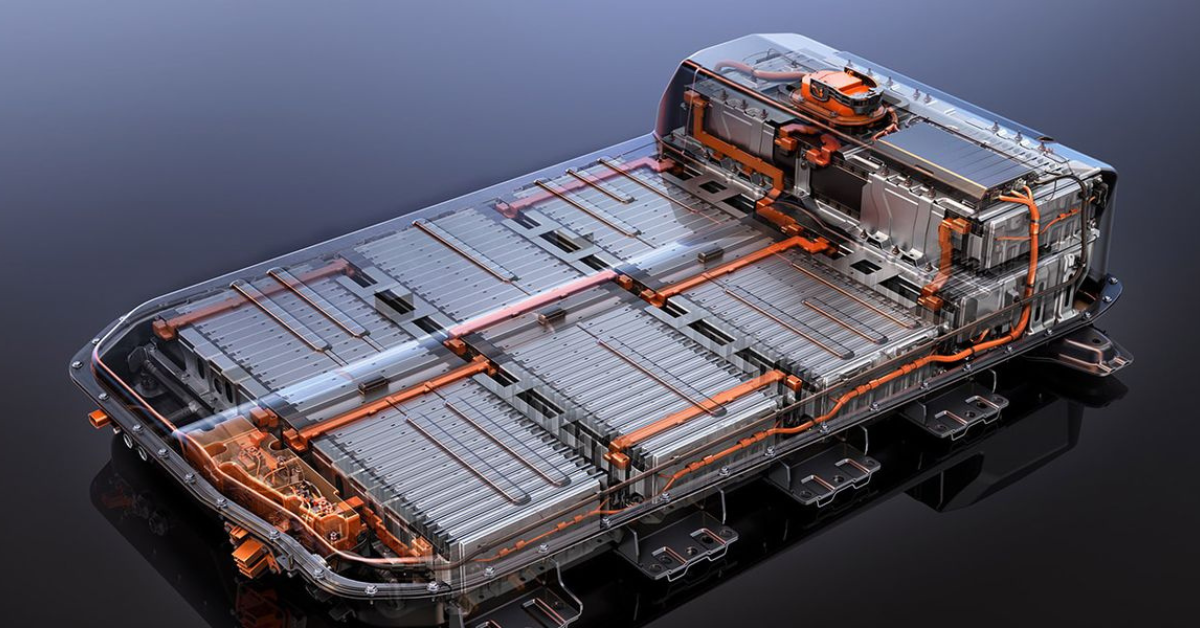

The challenges are numerous. Remanufacturing of modern EV battery packs is currently manual, a laborious, time consuming, costly process involving toxic and flammable materials together with high voltage hazards. The issue of liability may also make OEMs reluctant to release their packs for re-use to third parties, according to a 2016 study, Evaluation of a Remanufacturing for Lithium Ion Batteries from Electric Cars, led by Aachen University.

The solution, the study notes, lies largely in the packs being designed in the first place with remanufacture and re-use in mind: “A holistic design of the components, which considers modularity, interfaces and disassembly, is required. Synchronised components of the module, the cell bracing and wiring and housing is the first key to a remanufacturing able design.”

Unfortunately there is little evidence packs are being designed this way and no standardised remanufacturing process yet exists that could take advantage of such designs. Indeed this is a topic addressed in a 2017 paper. Called Development of a novel remanufacturing architecture for lithium-ion battery packs, the paper proposes a “remanufacturing architecture, which can handle a capacity of 5,000 up to 20,000 battery packs per year, depending on the selected degree of automation”.

The challenges in achieving a standardised - let alone automated - process are substantial. The uncertain quality of individual used battery packs and the variety of types (see box, Packaging EV power) and chemistries is one barrier to developing standardised and automated remanufacturing or reuse. Their varying quality matters too. The percentage of original energy capacity, which degrades over time, varies massively. Heat management systems also differ widely.

Open data

Data from battery management systems that can reveal how well looked after the packs were - and their existing health status - is another factor. Making such data openly available may necessary in order to make battery remanufacture and reuse viable, suggests the Scottish Institute for Remanufacture.

Vertically integrated Tesla, with its ambitions for a closed-loop battery life cycle, might be expected to be leading the way in overcoming these barriers. Yet it remains tight-lipped not only about the percentages of its vehicles that are recycled - but also the state of its remanufacturing operations in general.

When it comes to its batteries, the role and ambition of its remanufacturing operation (thought to number anywhere from 40 to 130 employees) is unclear. At the time of going to press, the manufacturer had not responded to ReMaTecNews’ requests for information on its remanufacturing and recycling processes.

Nor is there any news on Redwood Materials, a start-up linked to two top Tesla Motors executives, JB Straubel and Andrew Stevenson, that claims to be developing advanced recycling and remanufacturing technology.

Potential concerns

If anything, there are concerns that Tesla has barely started thinking about the potential for remanufacturing its battery packs. The early evidence is that remanufacturing of Tesla’s packs will be far from straightforward.

A spring 2018 teardown of the Model 3 by Munro Associates praised the sophistication and quality of the vehicle’s pack - but noted the lack of any apparent thought for disassembly either for remanufacturing or for easy recycling.

Craig van Batenburg, from the Auto Career Development Centre in the US, agrees there is little evidence Tesla has ‘designed in’ reman capabilities. The battery pack design seems to have moved on very little since his own teardown of an older Model S battery pack.

“It was moulded in a clear case with plenty of black plastic and glue. You had to cut and smash it to get the cells out,” says van Batenburg. “The wiring was well designed from a power and safety standpoint but not from a rebuildable design standpoint, by any means.”

Unclear future

He remains to be convinced about the scope or ambition of Tesla’s remanufacturing efforts in general, which might be thought to compare poorly with those in Tesla CEO and chairman Elon Musk’s other main venture, Spacex. “The only remanufacturing I see Elon Musk doing right now is of his rocket boosters,” jokes van Batenburg.

With global EV sales expected to account for a quarter of new car sales as soon as 2030 and more than half by 2040, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecasts, it seems likely a significant new remanufacturing market is taking shape.

But how it takes shape is unclear. At present it seems likely that the least degraded used packs might be re-assembled for reuse in EVs, while the older ones will be re-purposed and the rest recycled. Much depends on packs being made with remanufacture in mind - not something the automotive world seems to have devoted much effort towards so far.

Establishing automated or at least semi-automated pack remanufacture processes is another target - and a moving target, too. As the prices of new battery packs continue to fall (and they are so far falling faster than many had predicted), the challenge is to establish a battery remanufacture business model that will endure.

Reuse and recycling

As well as their potential for remanufacture, batteries can also be repurposed and a variety of approaches are being trialled.

Nissan UK has partnered with power management firm Eaton to re-use its packs for home energy storage and in Japan it is running a pilot which employs used EV packs to power streetlights. BMW and Vattenfall are exploring their potential to store solar energy at EV charging stations. Others, such as UK startup Aceleron, are exploring the potential for re-use of individual cells in e-bikes and as replacements for 12-Volt battery packs.

Repurposing may be the most economic use case right now, according to figures from Bloomberg New Energy Finance: 95 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of used lithium-ion batteries will hit the market by 2025 and of these 26GWh will be converted to stationary battery systems. (For context, Tesla’s Nevada gigafactory will eventually produce 35 GWh of batteries a year, enough for 500,000 electric cars annually).

The other potential route for old packs is recycling, which is a resource-intensive and laborious process, costing in the region of €1 per kilo - more than the value of the raw materials.

Tesla has claimed, however, that its historical efforts to recycle the battery pack of its debut model the Roadster with its partner Umicore at least have been profitable. How economic battery pack recycling will be for its current models will be anyone’s guess until the manufacturer shares more information about the forthcoming recycling operation at its gigafactory.

Packaging EV power

No common standard has yet emerged for the form factor and packaging of battery cells or of those cells into packs. Tesla is unusual in that it has opted for cylindrical cells (they look like standard AA batteries but bigger), which are well established in mass manufacture and widely used in laptops. There are thousands of these in each EV battery pack and each must be housed and wired in place.

Prismatic (boxy, rectangular) cells and pouch-style cells are more common in EVs and come in an array of sizes and capacities. Prismatic and pouch cells offer flexibility in the design of a pack and have potentially higher energy density by weight than cylindrical cells but are harder to prevent from overheating.

Remanufacture is likely to remain highly specialised and seems likely to resist any kind of automation until a common form factor and packaging process emerges.

Share your remanufacturing stories with us

Do you have an innovation, research results or an other interesting topic you would like to share with the remanufacturing industry? The Rematec website and social media channels are a great platform to showcase your stories!

Please contact our Brand Marketing Manager.

Are you an Rematec exhibitor?

Make sure you add your latest press releases to your Company Profile in the Exhibitor Portal for free exposure.